Slavoj Žižek begins his book Like a Thief in Broad Daylight by discussing the purpose of philosophy. Its purpose, he says, is to “prod” people – meaning to “corrupt the youth” the way Socrates did, by challenging established norms.

I like the word “extraneate” that Žižek uses, which means something like: “alienate” or “make strange.” For Žižek, the task of philosophy is to make the established norms seems strange so that it is more difficult to accept them, and more natural to question them.

Not all philosophy “prods” though: there’s another kind of philosopher who prefers to “normalise”, in the sense of keeping things in line with the status quo. (There’s a different sense of “normalise” in use now, which means something like “make a new normal.” We’ll come back around to that.)

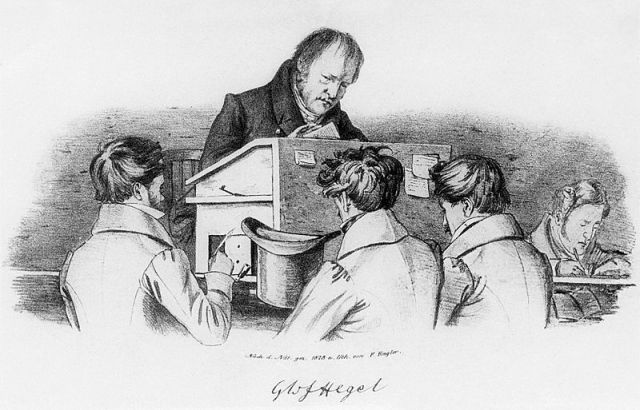

This “normalising” or “(re)normalising” philosophy Žižek calls “state philosophy.” Strangely, he doesn’t consider Hegel to be a state philosopher. “Hegel unleashed the all-destructive power of negativity,” he writes, and “even if [Hegel and others] sometimes appeared almost as state-philosophers, the establishment was never really at ease with them.” (1)

So being a state or (re)normalising philosopher means that the establishment is at ease with you, you fit into the established pattern, you don’t rock the boat.

Žižek, like all revolutionary thinkers, wants us to establish a new normal. It might sound like an old normal, since what he wants he is unashamed to call “Communism.” But for Žižek real Communism must always be something new, never simply a return to Stalinism, Leninism, or Trotskyism.

In the Introduction to his book, Žižek suggests that we look at all the “bad news” in the world today and try to find the “good news” in it. Looking for good news in the current situation doesn’t mean blithely accepting the status quo. It means looking for the possibility for change in the status quo.

For example, the “automisation of production” (human jobs being lost to machines) can be looked at in a negative, blithely positive, or radically positive way. On the negative side: it costs people their jobs, and risks throwing more and more people into poverty as their jobs are replaced and they can no longer find a way to earn a wage.

To find the good news in automisation is to ask yourself: why be afraid of automisation? Couldn’t it lead to a society where people have to work less and so are happier, more truly free? If you stop there then you’re just being naively optimistic: yes it could lead to that, but current political conditions suggest it won’t, since in fact automisation of production is used to generate more and more profit for a few, rather than to ensure that the mass of humanity have more leisure time, happiness, and freedom.

Looking at things this way can lead you into a kind of radical optimism, by letting you see what’s really wrong with automisation, which is not automatisation per se, but the fact that it is used to increase profits for the owners of industry at the expense of the working classes. The good news here is not in the facts as they stand, but in the possibilities that the facts open up: you can see now how political changes could lead to automisation being a good thing, and not “automatically” a bad thing. (6)

Žižek uses the rise of Jeremy Corbyn as an example of “good news” mediated by the “bad news”. In Corbyn’s case it was “bad news” in more ways than one: a “conservative media” portraying him as “undecided, incompetent, non-electable, and so on” made it seem that Corbyn might never be able to hold on to the Labour leadership. (9) But Žižek argues that all this bad news turned out to be good news: without the pressure of the media against him, Corbyn might have remained “a slightly boring and uncharismatic leader lacking a clear vision, merely a representative of the old Labour Party. It was in his reaction to the ruthless campaign against him that his ordinariness emerged as a positive asset, as something that attracted voters disgusted by the vulgar attacks on him.” (10)

What Žižek is talking about – and which I’m calling “radical positivity” – is using the possibility in a situation to bring a desirable situation about. But Žižek is quick to point out that things aren’t as simple as that. The truth is that you never know what the outcome will be in any given situation. You can merely try. There was no guarantee that Corbyn would survive the onslaught of the conservative media, but neither was there any chance of him surviving if he had blithely accepted the conservative pronouncements in the media and not stood his ground and fought back.

There are similar conservative judgements in the air when it comes to the possibility of Communism, and this brings us back around to the question of the two types of normalisation: normalisation versus what is more properly called “(re)normalisation”. Communism is often painted as if it were an effort in the latter, conservative direction: Communism doesn’t work, people say, and as evidence they point to failed regimes like the Soviet Union, as if it were to get back to that that communists wanted. But this is to ignore the real task of Communism, which is to bring about a new state of affairs, to make a new normal.

Žižek ends his introductory chapter by pointing out that the real goal of Communism, as stated by Marx, is abolition of the state. This, of course, has never been achieved. It might seem impossible to achieve, precisely because it has never been done before. In order to achieve their goals, communists must not look back at old regimes but look instead at the present, and at the possibilities that the “bad news” of the present day offers up to us.

(I’ve been reading Slavoj Žižek’s Like a Thief in Broad Daylight: Power in the Era of Post-Humanity, published in 2018 by Allen Lane.)